Sensory Case Study: Turku Museum Center in Finland

"Job Shadowing" at the Turku Museum Center

Earlier this year I traveled to Turku, Finland as part of the Erasmus+ program, where the Turku Museum Center was allowed to invite an expert to exchange ideas about multisensory storytelling techniques. I spent three full days there, exploring 6 museums and speaking with around 30 different museum practitioners.

We kicked off the week with a three-hour lecture and workshop, where I provided ways for the museum practitioners to apply and engage with their senses in real life. Here, discussion was key in order to better understand their concerns when using multisensory storytelling. For the rest of the week, the different teams took me through their museums to talk about how they were already applying multisensory storytelling to their collections, but also to explain their plans for the future. The museums were diverse in topic from medieval times to the present day.

Below I will outline some of the ways the Turku Museum is experimenting with multisensory engagement:

Experimental Scent Curation

Discussion around Olfactory Heritage and museums often comes down to one thought: museums are inherently occularcentric places. I still believe this to be true, but I was pleasantly surprised when the museums of Turku were quite the opposite. I was astounded by how the museums were already successfully applying multisensory storytelling - especially scent - to their collections as well as developing programming to increase accessibility and comprehension of sensory topics. Their effective and creative approach to experimental scent curation in particular made me realize that where there’s a will, there’s a way!

Example from the Pharmacy Museum and the Qwensel House:

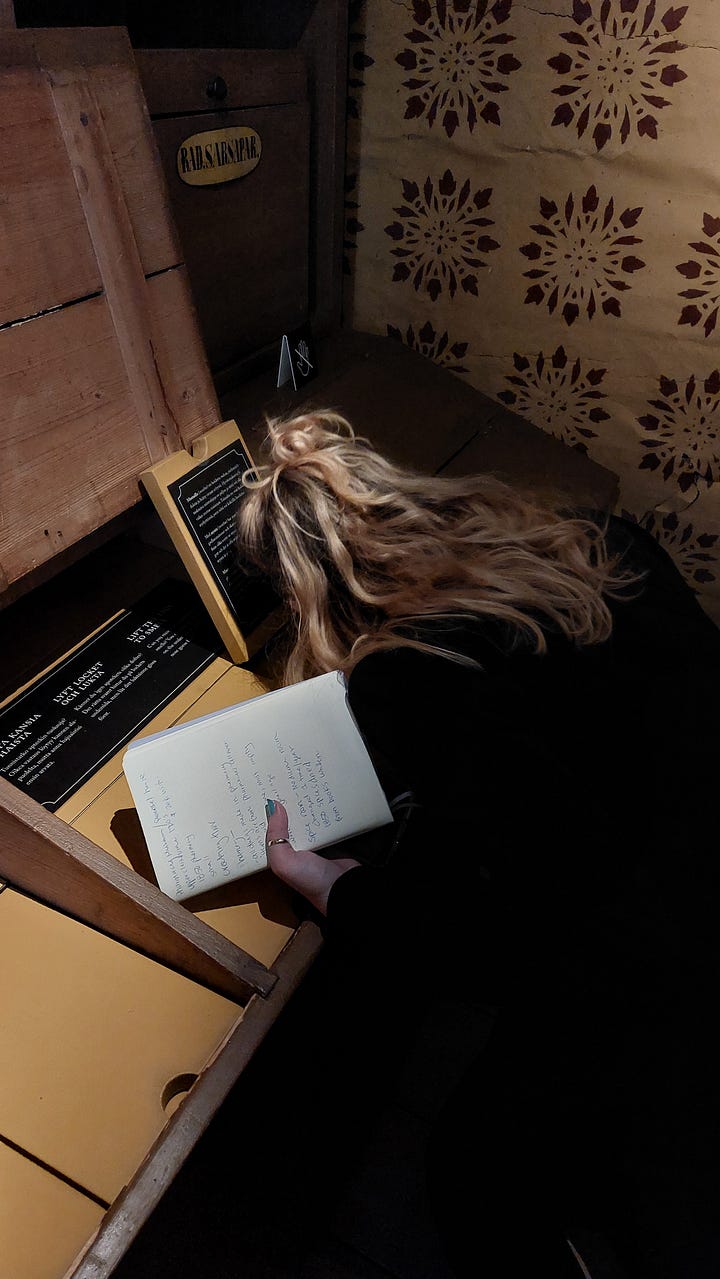

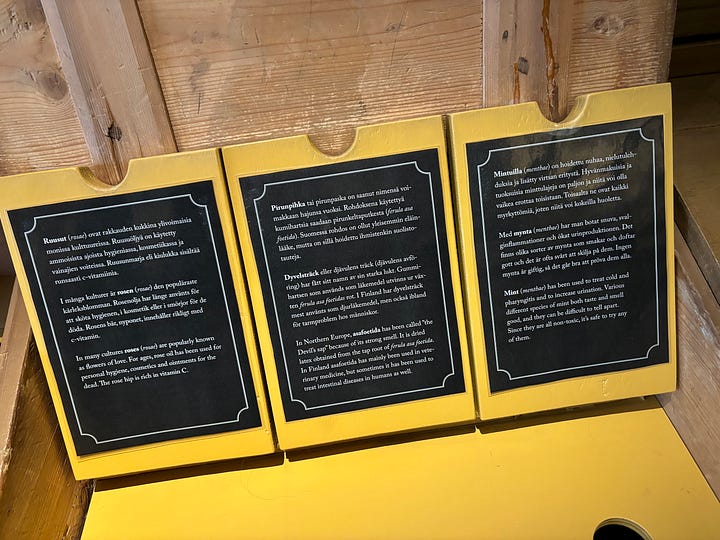

To educate about the important role that herbs and spices play in Finland’s pharmaceutical history, the museum curators dedicated a room display to herbs and spices. Here visitors are welcomed into a pleasantly fragrant room where locally sourced, dried herbs hang from the ceiling. Small placards hung with each of the herb bunches had a text explaining the cultural significance of the herb and its use.

In the same room was a specially designed “scent station,” where visitors could sniff six different scents. The low fuss scent station was made of upcycled jam jars with a paper towel inside on which essential oil can be applied as needed. This instance of olfactory storytelling supported worthwhile storytelling, as the scent was grounded within the context of the museum’s themes and educational content. Scents were adequately described via short and informative texts.

Example from Luostarinmäki 1827 Open Air Museum:

Luostarinmäki is an Open-Air Museum that presents how life was in the area during the 1800s as authentically as possible. Real life includes all the senses; therefore, the museum includes sounds and smells in the various themed rooms. My favorites were the scented materials that the curators had hidden in the different rooms. For example, the piece of wood with turpentine that was discreetly tucked behind the entrance door. The faint scent off of the wood was just noticeable enough to highlight some of the aspects important to the craft of furniture making, which was carried out in that room. Another example was the tarred rope that represented Turku’s rich maritime history. Again, the significance of these scents and their connection to the themes and content of Luostarinmäki were directly highlighted in the descriptive texts that visitors could read for each room.

Hands-On Art

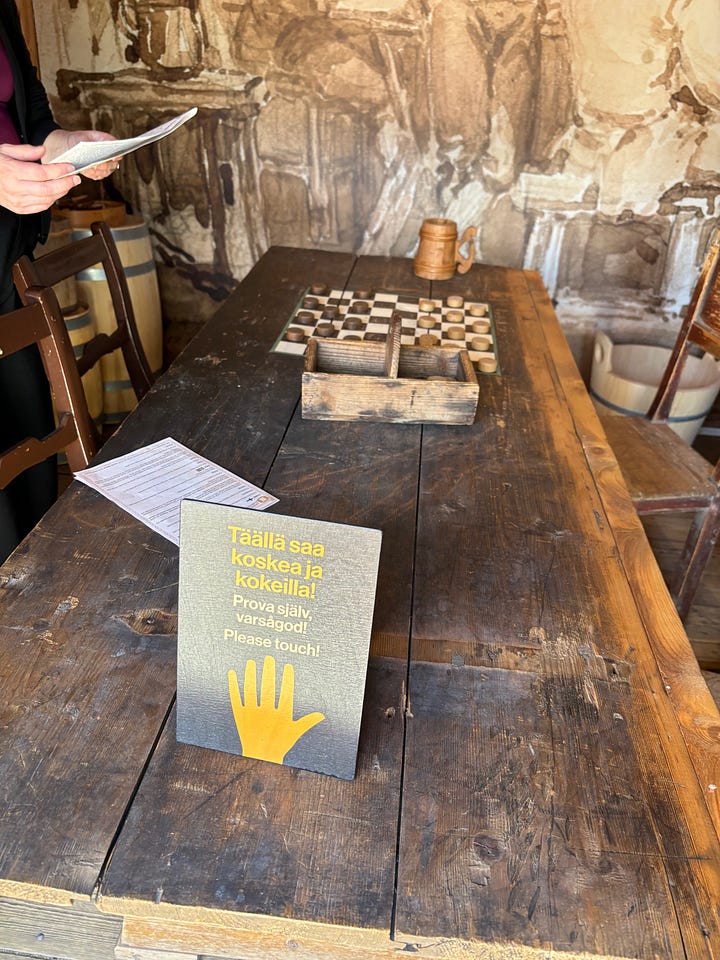

The Turku Museum Center team also wanted to introduce more tactile methods that engaged their visitors. The museums were already experimenting with 3D printing and using collection items to give a sense of atmosphere.

Presentation from WAM (Museum of Modern Art):

To spark brainstorming, the museum educators and curators from the WAM museum organized a tactile presentation for me. They chose different artworks in their collection that they would like to present to visitors and paired them with various materials. This initiated a very productive conversation on how these modes of interaction can be organized in practice.

Main Takeaways

This experience was extremely insightful, and I learned a lot from the team at the Turku Museum Center. I would like to share the following takeaways:

Firstly - as can be seen above - many museums are already successfully and efficiently applying methods of multisensory storytelling. This begs the question: are museums indeed occularcentric places or have we just not identified the plethora of museums like the Turku Museum who are already experimenting sensory engagement?

Secondly, museum professionals want practical and easy methods of using multisensory storytelling that they can apply quickly. The quick and easy methods of olfactory storytelling applied above echo this point. However, these methods still require a bit of TLC. I found that the museum practitioners lacking information about the management of olfactory materials, such as how often to clean and replenish scented vessels. It may seem like a small detail, but it can greatly affect visitor experience.

And lastly, not all museums are made the same. This may seem obvious but a key learning point for me, as it emphasized that challenges of multisensory storytelling can vary by the museum that is applying it. Some museums have collections they want to protect behind glass, while others have their collections displayed outside in all weather. Some museums have a team of two people, while others have a team of hundreds. The capacity of a museum can greatly affect the scope of the olfactory event.

A special thanks to Susanna Hujala, Maria Huokkola and Eveliina Tammi for the invitation and to the rest of the Turku Museum Center team for being such gracious hosts.

Are you a museum that would like to share how you use multisensory methods to engage your visitors? Feel free to reach out at thesensesationalexplorer@gmail.com!